Our Travel blog

When I was about 14 I was afforded a position of rare responsibility at school. Together with my friend Julian we carefully fostered the impression that literature held an interest for us so that we could gain accreditation as library monitors. In truth Julian had discovered some saucy text in a book and was eager to find more and I wanted clandestine access to the school Xerox machine to print a fanzine I was involved in putting together. After a serious talk from Mr Leonard about the importance of our role and the mighty responsibility upon our tender young shoulders we were largely left to our own devices. Pretty soon my hands were stained blue-black from my surreptitious printing and Julian’s were rubbed raw. After a while it dawned on us that we should probably do a little light librarianing from time to time if we wanted to retain our positions. And as Julian had just discovered the D H Lawrence section he was eager to continue and I was getting a growing reputation for my nifty way with a cumbersome Xerox machine. The problem with our escapade was that neither of us had paid any attention to Mr Leonard’s induction. We had a vague idea that cataloguing was involved but until now we’d contented ourselves with just sticking the returned books back where there was a space. The delights of Dewey or Universal Decimal Classification were unknown to us. The Library of Congress system was a mystery and the Colon classification was probably something bored proctologists indulged in. I don’t recall the detail now but one day while sorting some returns onto a shelf we chanced upon our own system that was aesthetically pleasing, simple and absolutely unique. This would put Leiston High School on the map. In our minds eyes we saw the headlines in The East Anglian Daily Times hailing two local schoolboy heroes. On my way home that evening I was rehearsing my first radio interview and wondering what to wear when the TV crews came calling. The following day we set about our plan, spending as much time as possible avoiding lessons and keeping 3rd years out while we rearranged the books to our satisfaction. Sometime around mid-afternoon we stood back, arms folded and admired our handy work. Julian disappeared to the lavatory with a copy of Cider with Rosie to celebrate while I made some small adjustments and tweaked the odd spine into its exact place. With the passage of time I’m unsure if we summoned Mr Leonard or if he just appeared but I do distinctly remember being rather hurt at his reaction to the school library being rearranged into colours and then height. We thought it provided a much more appealing vista as you entered and cheered the gloomy place up no end. Indeed I’d go so far as to say it was a vast improvement upon the former higgledy piggledy mismatched chaos he’d left behind that morning. He wasn’t angry exactly. It was more an uneasy calm that comes somewhere on the icy plains beyond mere anger. He stood gaping and trying to start a sentence without success…”but…” (silence) “I mean why would…” (slow shaking of head) “how would you find…” (silence) “why…why…” (claps hand to forehead) “I thought you understood…” (flapping of arms) “I don’t know what…” (silence) “Why would you do…” then, turning first to me then to Julian he whispered “What were you thinking…why would someone do this?” I learnt a valuable lesson that day about rhetorical questions. With hindsight I probably shouldn’t have launched into such an enthusiastic explanation of our system; one that gradually withered under his gaze until I stood silently looking at my grubby shoes. Our punishment was to put everything back, which given that we had to use a cumbersome system that involved reading faded numbers on the spines and occasionally looking through microfilm records to cross reference volumes took a lot longer than we had spent on our reorganisation. We felt it was unwise to point this out to Mr Leonard on one of his frequent visits to check on our progress, even though to this day I maintain ours was the superior system. All of which may explain my absolute joy on discovering Craignure’s lone charity shop has an entire bookcase of second hand books arranged by colour. I bounded up to it overcome with rapturous delight. “Behold” I exclaimed turning to face Alison with a sweeping gesture towards the magnificent display. Considering that Alison has just spent an entire winter re-cataloguing a theological library she controlled her enthusiasm with commendable fortitude and walked away shaking her head. I did note that their neatly coloured book shelves were a bit untidy but I can just imagine their delight when I pop in every day to tutor them on the correct application of the system. Mull, we need each other!

0 Comments

You know what it’s like; you send a few speculative emails off in response to job ads looking for seasonal staff and next thing you know you’re driving to a remote castle on a Scottish island for an overnight stay that will include sunshine, wildlife, 40mph winds, cancelled ferries, snowcapped mountains, meeting aristocracy and an 800 mile round trip. After last year’s adventures we haven’t really settled down. Our house is lovely but we don’t get to use it very much as we spend most of our time in a ‘grace & favour’ apartment at work. After much agonizing we concluded that another carefree summer on the road just isn’t practical and we needed an alternative, something that would satisfy our wanderlust and still provide us with a modest income, or indeed an obscenely large income should the opportunity arise. We’re really not sure quite how it came about, since I was supposed to be researching vets at the time but an email was sent to Duart Castle in Mull, some correspondence was exchanged, one thing led to another and one sunny Sunday afternoon in March we loaded the final bag into Mavis and set forth for Scotland’s second largest Inner Hebridean island. Our first destination though was Strathclyde Country Park where our previous adventures north of the border started back in May 2016. The site is run by the Caravan Club, although they have since renamed themselves the Caravan and Motorhome Club in a bold move certain to incur the displeasure of traditionalists and the more conservative of their clientele. The message boards on the clubs website are full of unenthusiastic comments about the new logo, the re-branding exercise in general and indiscreet digs at the club. As is usually the case with message boards and website comments the same names keep popping up like passive aggressive moles. After a while you start feeling sad for them, locked in their own little bubble of insignificance, desperately trying to assert some semblance of control over a scary unfeeling world. After a couple of minutes in quiet contemplation I decided I couldn’t give two hoots about it and left the disenfranchised to their empty threats of boycotts and defection to other clubs. The journey had taken us from the dull monotony of the M6, through the pass between The Lake District and The Yorkshire Dales and upwards to the border where the M6 gives way to the M74 and the landscape changes from the verdant greenery of northern England to the muted greens and russets of Southern Scotland. It’s like the same rain that fed England and made it so lush washed away the colour from the north side of the border. While Alison drove I dozed in that undignified way that gentleman of a certain age perfect, snorting, dribbling, guttural grunts and occasional whimpering. I woke in time to casually deflect a string of drool from pooling in my lap as we were starting the long descent into Glasgow. To our right ugly tower blocks had been given a makeover, bathed in gentle light and given decorative ‘lids’ to hide whatever is necessary to plonk on top of a tenement block; water tanks and lift machinery I suppose. I’ve no idea what they are like inside but however you gild them they will always be the option for those who have little or no choice, intimidating columns of humanity stacked on top of each other and placed on the margins, literally and figuratively, of the city. That said I worked with some amazing people who lived in the tower blocks in Tilbury and swore by their community spirit and homely flats. But no amount of fancy paint and concierge services could disguise the menacing atmosphere nor negate the need for a suite of back room offices dedicated to maintaining the security of the three towers, including a dimly lit room with banks of TVs carefully monitoring every corridor, lift and entrance to the buildings. We were greeted in Strathclyde by a friendly Welsh Warden who made us feel instantly welcome. It’s the little touches that count, like giving us a temporary fob for the gates so we didn’t have to go back to her hut and exchange our pitch number for a correctly numbered fob, as we’d be leaving early in the morning anyway, which was probably just as well because she’d have had a long wait. We were faced with an almost empty site. In theory this gave us a fabulous choice of pitches. In practice we froze, unable to decide. On this chilly evening we eventually elected for a pitch close to the shower block and the ‘should-we-drive-front-in-or-reverse-do-we-need-chocks-right-hand-down-a-little-NO-your-other-right-back-a bit-back-a-bit-straighten-up-no-the-other-way-STOP-forward-a-bit-sorry-I-forgot-the-chocks-back-a-bit-maybe-we-should-try-facing-the-other-way-sorry-dear-this-is-fine-do-you-think-we-should-have-filled-up-with-water-first?’ dance began. Once we’d remembered where everything was onboard Mavis and had brewed a welcome cuppa we appraised our options on this chilly Glasgow evening and elected to take refuge in the nearby Toby Carvery. And very fine it was too. Hard to wax lyrical about a chain restaurant but it was reasonably priced, the food was served in generous portions and the staff were attentive and friendly. Duly sated we waddled back to Mavis and settled in for an early night. Before we went to bed though we were chatting and in response to a rather lame joke we both got a fit of the giggles. Suddenly the tension of the drive, worries about what we might find, whether we were doing the right thing, what our families might think, all our unspoken anxieties exploded out as we wept with laughter, doubled over in painful ecstasy. I woke at 4:30 am, slightly ahead of the alarm and sufficiently disorientated to forget about the ladder down from our sleeping quarters until gravity reminded me somewhere half way down. I managed to land feet first and turn my clumping decent into a nifty pirouette ending at the bathroom with, I suspect, rather less elegance than I imagined. After braving an early morning shower we hit the road and the first stop was a 24hr garage to re-fuel. Alison went in to pay and the attendant couldn’t have been nicer if he tried. A rare skill at 5am but even so his demeanour and language was pure Glasgow grit. The accent is harsh, clipped and delivered at a pace even fellow Scots find hard to fathom. A cheery “have a nice day pal” sounds like a threat and “nay problem” an abrupt sign off to a casual enquiry. In truth we were shown nothing but helpful courtesy by Glaswegians even if it was delivered like a warning. We took the motorway through Glasgow, busy even at this hour, and into the Lowlands leading into the Trossachs National Park and the joy that is the drive up the Western shore of Loch Lomond. As the darkness turned to a watery grey and into the pale blue of dawn, mountains on the eastern shore loomed out of the early haze and the waters of the loch rippled and shivered in the chilly early light. On the higher peaks fingers of snow lingered, shaded from the sun in the rivulets and gullies. Below the land was pale with fallow grass and bronzed with last year’s bracken. Rain lashed down spasmodically, driven across the loch by fresh winds, shaking the trees on the bank and giving the road a sheen that reflected the lights of oncoming vehicles. We watched the loch come alive through the soft focus lens of the windscreen until we turned right at Tarbet, where the road hugged the shoreline and Mavis swung around bends millimetres from overhanging rocks softened by lichen and moss. And so we trundled on. Sunlight lit up distant hills and mountains while we drove through drizzle. We bounced over roads potholed from the winter freeze and cruised on brand new tarmac still steaming where neon clad workmen swarmed over once yellow trucks laying new carriageway over the old. After the splendour of Loch Awe and the sparsely populated hills we passed through managed forest that gave way to open countryside as we met Loch Etive and followed its southern shoreline all the way to Oban. At nearly 20 miles long the Loch drains the hills and mountains around Glencoe and deposits it into the sea at Connel, where the landscape changed again and we started seeing signs of more settled habitation; bungalows lined the road as the wilderness gave way to the outskirts of Oban. After a hair rising decent we rounded a corner and joined Oban’s rush hour streets. Despite the snail paced final mile we arrived at the ferry terminal in good time. We should take this opportunity to state that, without exception, every encounter we’ve had with CalMac Ferries staff has been cheerful and polite. Not in a supermarket checkout scripted kind of way but genuinely efficient and friendly. For reasons that will unfold later we were to have bad news relayed to us later on this trip by a member of the CalMac team and even then they made us smile. The ferry crossing took 45 minutes from Oban to Mull and after a light breakfast onboard we took to the windy port side deck to catch our first sight of the sombre Duart Castle on its rocky outcrop. Incidentally port side is the left. I’m not sure why nautical coves insist on their own terms for left, right, pointy bit and blunt end but there you go. Once we’d disembarked we ventured inland a bit and made a brew overlooking the quiet Loch Don. From there we negotiated the single track A road, turning off onto a road only slightly wider than Mavis. Moss covered stone walls lined the route giving way to tumbling grassy slopes to our right and straggly bare trees that allowed tantalising glimpses of the cloudy blue of Duart Bay and the castle perched on its lonely promontory. Drawing up to the castle the road widened and fed into a tidy carpark where a single car was disgorging a heavily coated couple onto the windy headland. Duart Castle was sombre but the welcome we got was warm and cheerful. We were shown around, poked about in the tea shop, admired the cannon studded formal lawns, peaked into the castle and enjoyed a cuppa with our host. Afterwards we wandered around the grounds, scrambled along rough paths and admired the views across the bay and over to the mainland. Its isolated position made Duart seem both imposing and inspiring. Menacing dark clouds drifted over the open waters and a swirling wind was funnelled between the mountains and hills on either side of the choppy white flecked Sound of Mull. Gulls rode the breeze behind a lone fishing boat that ploughed a silvery channel in the water as it chugged towards the mainland. Left to our own devices we swung Mavis into the campsite overlooking Craignure Bay where we pitched on the waters edge looking out over the bay. We hadn’t forgotten our pitching up routine and swung into action, unfurling the electric hook up cable, turning gas on, unpacking essential equipment inside and generally turning Mavis from 3½ tonnes of travelling warehouse into a compact home. It was wonderful to be back aboard. We relaxed and eased into a meditative state, reading and supping tea while lost in out private thoughts about the idea of living and working on Mull. Throughout the afternoon and evening we looked around Craignure, walked around the shoreline and cooked our supper. It was all done while batting pros and cons between us or mulling them over in the echo chamber of our private thoughts. As darkness gathered and the lights over the bay and on the mainland twinkled into life we ate and slid into bed, thankful for a pause after a long and taxing day. We’d just nodded off when the winds that had been gathering all evening started blowing in earnest and Mavis started rocking on her axles. (I’ll pause here for you to insert your own smutty joke…) 40mph winds are classified as “a fresh gale” on the Beaufort scale. We can testify that they were certainly fresh, buffeting the sides of Mavis and rattling the fixtures and fittings at irregular intervals. Outside the sea was eerily calm, reflecting the swaying yellow lights strung out around the other side of the bay and lapping against the rocky foreshore in front of us with a gentle rhythm that was at odds with the squalls pummelling us. We eventually sought refuge lower down and made up the spare bed where we spent a fitful night. The morning was bright, the wind calmer and the air fresh and salty. We stretched our aching limbs and undertook a cursory inspection that showed Mavis had weathered the storm unharmed. I survived the shower block, rudimentary but efficient and warm and we took ourselves off to the island’s de-facto capital, Tobermory. Fans of the children’s TV program Balamory will know it well as it doubles as the eponymous fictional community. It’s an endearing place of colourful houses and shops spread around a horseshoe bay. Now is not the time to dwell upon the pretty town, nor indeed the splendour of the island, and it is certainly splendid, with mountains, lochs, historical sites and wildlife that includes otters, whales, basking sharks, red deer and two types of eagle (White Tailed and Sea) and many other attractions. Hopefully the photos will do it some justice for now. On the drive back from Tobermory we decided that whatever happened we would return, either to work over the summer or just for a visit and with that promise I shall dwell no more upon the sights. Before returning to work at Shallowford we had one final challenge to overcome. Upon presenting ourselves for our afternoon ferry back to Oban the nice man in the CalMac office informed us that it was cancelled owing to the high winds and waves but the much shorter crossing to Lochaline was running and was making continuous runs to cope with the increased demand. Thus we queued up for the small ferry, a roll-on roll-off landing craft which held around 8 cars and vans. We had an hour to wait so we made some soup and discussed the opportunity before us to live and work on Mull until our time came to bounce noisily over the steel plates and onto the slick deck which smelt of diesel and damp. We rolled over the waves for 20 minutes and into the tiny settlement of Lochaline, marooned on a peninsula beside Loch Aline. The drive took us along the narrow undulating A884, and when I say narrow I mean single track with passing places and the ever present threat of meeting a fully loaded logging truck chugging up a hill or hurtling down from the summit seemingly out of control. And a word here for a local custom that actually made Alison squeal with delight. To avoid locals having to drag along behind slowcoaches like us the well informed motorhomer uses the passing places to pull in and release them to go about their business at a more urgent pace. One’s reward for such good citizenship is a friendly ‘toot toot’ as the car pulls away. Well, to her delight, Alison collected many toots; I think we were up to around 15 plus a smattering of hazard light flashes by way of gratitude - not as rewarding as a toot but still gratefully received. Only one car just sped grumpily on without acknowledging us. I don’t need to tell you by now that it was an Audi do I? We had one more short ferry crossing to negotiate, across a narrow point on the vast Loch Linnhe, from where we drove on into an area familiar to us from last year’s travels, up through the pass at Glencoe and through the bewitching tan wilderness of Rannock Moor, its dark pools of peat rich waters reflecting the silvery grey sky, and down to skirt Loch Lomand again. Here we swapped driving duties and eventually pulled into Shallowford at 2am. Too tired to bother about going indoors we wearily climbed into bed in Mavis and immediately fell into a deep and dreamless sleep. It’s now a fortnight since we visited. We’ve had many discussions, weighed up the pros and cons, gone back and forth with questions and answers and finally made a decision. To be continued…after the photos.

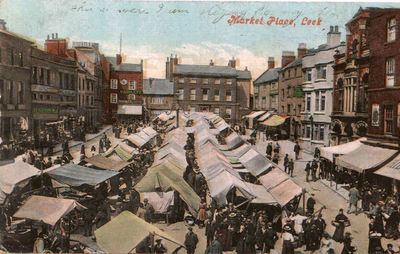

Yup, we’re going to work in a medieval castle on a Scottish island. Mull, here we come! (Just for four months though - May to September)  What do darts champion Eric Bristow, Dave Hill, vocalist with heavy metal legends Demon, the founder of the Arts and Crafts movement William Morris and James Ford, one half of electronic duo Simian Mobile Disco and producer of artists including Artic Monkeys and Florence & the Machine have in common? Well, they all live in or have close ties to Leek in Staffordshire. Of course a chubby bloke who throws pointy things and thinks victims of child abuse are not ‘proper men’, a couple of musicians barely known outside of their front door and a revolutionary socialist designer of flowery wallpaper hardly make Leek the epicentre of culture, but it’s something. Morris visited in 1875 and stayed on and off for three years with his friend Thomas Wardle, a silk dyer who operated the Hencroft Works in Leek. Labouring together they improved organic dyeing techniques for textiles, the racy pair of scallywags. Importantly though, Morris had his eyes opened to the conditions the mill workers had to endure and his time in Leek influenced his left leaning politics, although paradoxically his designs found patronage among the middle and upper class or as he as he put it "ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich". Before Morris swaggered into town Leek had already played its part in revolutionary politics. During the civil war it was staunchly Parliamentarian, driving those pesky Royalists away and the local garrison played its part in the fall of Stafford. Later, in 1842, Josiah Henry, a 19 year old shoemaker from the town was shot through the head and killed by troops at nearby Burslem. Josiah had been among a ‘mob’ of Chartists, marching and generally rioting in protest against their poor working conditions and the corrupt political system of the day. Stoke and the potteries were among a number of poor industrial areas where the Chartist movement took root. Their demands were not unreasonable by today’s standards:

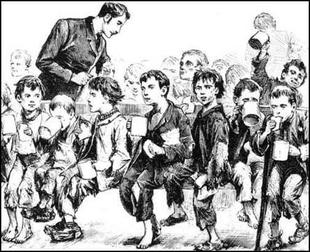

As you can see we meet or exceed all bar the last one nowadays and I for one am happy to avoid the administrative burden and expense of annual elections. Poor Josiah was, at just 19, a widower with 3 young children when he was felled protesting against corruption and injustice. Not much else seems to be known about his circumstances but the silk mills, which by the end of the 18th century employed around 2,000 people in the town and a further 1,000 in the wider neighbourhood were notoriously grim to work in. Significant portions of the workforce were children, often from local workhouses. High numbers of orphans meant local authorities were only too willing to place the children in the care of the mills to save them the expense of raising them. In the mill they would begin work aged around nine in return for food, lodgings and if they were lucky one hour of schooling a week. The hours were long and the work unpleasant and at times downright dangerous. The Macclesfield Courier printed this in May 1823, “A little girl about seven years of age was caught by her clothes and drawn between an upright shaft in the engine room and a wall…..life was extinct”. It’s just one of many such entries in the local press of the time. As if the hours weren’t punishing and the conditions weren’t hellish enough, the children were controlled by brutish stewards or ‘overlookers’. On 23rd November 1833 The Macclesfield Courier reported on the death of 11 year-old Sarah Stubbs, who worked as a ‘piecer’ in a Macclesfield mill, the inquest revealing that she was repeatedly beaten for not tying broken silk threads at the required rate. The work of children was sanctioned by law. The Cotton Factories Regulation Act of 1819 set the minimum working age at 9 and maximum working hours at 12 and later the Ten Hours Bill of 1847 limited working hours to 10 for children and women. Ironically in the early 1800’s the silk mills were considered relatively benign places for children to work, to the extent that they were exempted from the child labour laws for a time. Looking back on it now the children working in the coal and lead mines were worse off but when we’re talking about 10 year olds it’s all relative. It’s worth pausing here to note that the appalling working conditions children had to suffer in this country up to the 20th century are still endured by children around the world today. According to The International Labour Organisation the global number has declined by one third since 2000 but there are still 168 million in child labour with 85 million of those in hazardous work. Article 32 of the UN Convention on the rights of the child states: “Governments must protect children from economic exploitation and work that is dangerous or might harm their health, development or education”. I fear though that the UN article may just be a nicely worded piece of spineless liberal guilt. Case in point; as well as the 45 Articles there are 3 additional protocols that are optional; governments that ratify the Convention can decide whether or not to sign up to them. The protocols are: the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography, the involvement of children in armed conflict and a complaints mechanism for children. Just to be clear then, it is 2017 and selling children, involving them in prostitution and pornography and sending them to war is optional. FFS! Back in the 1800’s a Parliamentary enquiry eventually uncovered and publicised some of the unsavoury conditions which did lead to improvements. Nevertheless children were still employed until the Education Act of 1880 introduced compulsory schooling up to the age of 10 and child labour began to dwindle. Subsequent amendments raised the school-leaving age to 12, with dispensations to leave before this age if pupils reached the required standards in reading, writing and arithmetic. By the end of Victoria's reign, almost all children were in school up to the age of 12. I’ll give the last words about it to 10 year old Samuel Downe, giving evidence to a parliamentary enquiry in 1832. ‘We used to generally begin at five o ’clock in the morning till eight at night’. When asked had he received punishment he replied ‘yes, I was strapped most severely till I could not bear to sit upon a chair without pillows, and I was forced to lie upon my face at night. I was put upon a man’s back and then strapped by the overlooker’. When asked why he was punished he replied… ‘I had never been in a mill where there was machinery, and it was winter time, and we worked by gaslight, and I could not catch the revolutions of the machinery to take the tow out of the hackles; it requires some practice and I was timid at it.’ One thing the mill owners did do towards the turn of the century was build housing for the workers and their families. Thus by 1878 Livingstone Street in Leek was on the map, typically industrial red brick housing of 123 mostly terraced abodes, each with a small yard complete with privy backing onto a cobbled alley. The cobbled alleys are still there, as they are all over Leek, glorious in their evocation of a bygone age. But lest we sentimentalise too much, today Livingstone Street has mains drainage, indoor plumbing, central heating and refuge collection. We have now made one of these former workers houses our home, extended sometime in the intervening years to incorporate a bathroom and a nice kitchen with gas at the flick of a switch rather than us having to fetch coal in for the range. I’m under no illusions about coal fires and range cooking. We had coal fires when my parents moved us to Suffolk. Bewitching as the crackling flames and flickering glow was the fire needed careful nurturing all evening and only heated a semicircle of our living room to a radius of about 3 feet; anything inside the heating zone would steam and wither while anything outside froze. I spent many a winter evening on the threshold of the magical sector slowly revolving like a chicken on a rotisserie. Every 15 minutes or so a plume of acrid smoke would puff back into the room where it joined the fug from my father’s cigars to make my eyes sting and add another layer to the brown patina of the ceiling. On a bad night I’d bend double and cough up my dinner while my hair singed and my bottom turned to ice. In between these smoky interludes I kept busy trying to avoid the red hot embers the fire would occasionally spit out. These tiny volcanic bombs would burn on contact with flesh, burrow a smoky trail through clothes and occasionally ignite the dog. My school blazer looked like it belonged to a clumsy chain smoker who lacked opposable thumbs. Garments dried on the old wooden clothes horse in front of the fire would crisp and stiffen up like board. I once made my freshly dried trousers stand up by themselves and then balanced a shirt on top to create a freestanding dummy fresh from the clothes horse. Well, it was a long winter and there wasn’t much else to do. We had one radiator in the house, essentially an overflow for the coal fired back boiler in the range. It was in my bedroom and worked a treat, so long as you didn’t mind acrid desert conditions all summer and artic winters. If I turned it off in the summer the whole system would rumble ominously and steam would escape from mysterious valves in the bathroom. If I turned it on in winter my room just got colder. The whole system was a mystery to my parents and, it turned out, to the local plumber too. I woke up one morning to a fountain of scalding water arching across the room onto my bed. The plumber turned lots of valves and taps that had no noticeable effect, hit pipes with a hammer and generally walked about the place looking bemused. Eventually he repaired the radiator with some sort of putty and what looked suspiciously like a used bandage and I was advised to move my bed further away. My mother used the coal fired range for cooking, which meant it cooked with the power of a match under a cauldron or with the heat of a medium sized star. Added to this was her charming belief that the food would be ready when she was, in spite of the wildly fluctuating temperature of the oven and her aptitude for getting distracted. Remarkably dinner was always ready at 5.45pm. If, that is, we accept the premise that ‘ready’ means it’ll be served up in whatever state it happens to occupy at 5.45pm while on its haphazard journey from rare to carbonized. So, we’ve decided against open fires. In other respects we have a mission over the coming months to undo some of the more flamboyant DIY a previous owner has attempted and to do a little light decorating here and there. But it’s a great place to live, cosy and homely and the toilet is inside. Sitting on major trans-Peak roadways Leek has long been a transport hub. The major roads had lucrative turnpikes and it was connected to the canal system as a branch of the Caldon Canal, which closed in the 1940s. The railway lasted until the 1960s when Dr. Beechings got his grubby hands on it. A street down from us now houses the bus station and an ugly parade of 1960s shops well past their prime, built on the site of the old cattle market. Just along the road things improve dramatically however. At the foot of the High Street is the Nicholson War Memorial. Built in 1925 and clad in pale Portland stone it stands an impressive 90 feet high with a large clock face on each of its four aspects. Over the road from the memorial the high street crowns the hill Leek sits upon, with an ancient market square at its apex. Granted a charter to hold a market on Wednesdays during the reign of King John at the beginning of the 13th century the market is still a regular local fixture. The High Street came second in the Telegraph's High Street of the Year in 2013, losing out to Deal in Kent. I’m not sure it would do so well now, it’s not gentrified like Southwold or touristy like nearby Buxton, but its charms are still there in the details; original wooden hitching posts along the street, the cobbled market square, independent shops and cafes, a surfeit of busy pubs and echoes of the arts and crafts movement heralded by William Morris. Look up as you walk along the high street and there are fine stained glass windows in unexpected places, examples of elaborate plasterwork above anonymous shops and little architectural gems down narrow alleys and side streets. Just past the market place there is a large civic park that drops away dramatically from the sombre St. Edward the Confessor church into a narrow gully and rises again through woodland to less formal lawns, a bandstand and tennis courts. It’s most comely in its sprawling semi-formal way, a nice contrast to the rugged moorlands that lay beyond. From the high points you can see the chimneys and spires of Leek over the trees. Although it’s on a hill Leek appears to sit in a bowl surrounded by the higher Staffordshire Moorlands and Peak District to the North and gentler hills to the South and West. Eastwards lay the heights of Mow Cop, which you can read about in our entry from 7th June 2016 if you feel so inclined. It’s an interesting place in an industrial heritage kind of way. It’s no Florence of the Midlands but architecturally it does wear its manufacturing past well. Some streets close to us are still cobbled, abandoned silk mills pop up around street corners, some converted into offices and warehouses, some apartments and others sit abandoned and derelict, casting sinister shadows over the surrounding houses. These are ripe for re-development; when we were looking for a place to buy we were shown round an apartment for sale inside the converted Waterloo Mill and it was stunning with high windows and great views. It was gratifying to see the building preserved and repurposed. On a drab wet Tuesday recently we walked to the Sainsbury’s store on the edge of town. It is down the hill from the town centre, on the banks of the River Churnet and next door to Brindley Water Mill, an 18th century corn mill that’s still in working order. Standing in the drizzle on open ground between these two contrasting buildings we could see the open moorlands curving around us capped in fresh snow, the line between grass and snow almost ruler straight. Before the hills lay lush green pastures topped with barren winter woodland and stone farm buildings on level ground hewn out of the tumbling countryside. It reminded us that for all the necessity of convenience foods and toilet roll what we really needed was to get out into that open moorland with a backpack, map and trousers with too many pockets in. But, we both silently concluded, when it’s a bit warmer. Walking back we diverted by the back streets, rows of terraced homes like ours which revealed another of Leeks charms; small out of town shops and businesses. This was a real revelation. Nearly every residential street has a corner shop of some variety. Some are convenience stores, some chip shops, others bakers, sandwich shops and more than any other, hairdressers. Maybe it’s the windy conditions that force the population to get their hair done so regularly. I counted 36 different hairdressers on one website and that doesn’t mention a few that we’ve passed on our explorations. In keeping with hairdressers everywhere they excel in crappy pun names. Our favourite thus far is “Curl Up And Dye”. I just love the idea that small, almost micro businesses are so prolific in a town with at least 6 main supermarkets in or around it. Worth a mention here is our local Oatcake shop. For those unfamiliar with the culinary phenomenon that is the Staffordshire Oatcake it’s a savoury pancake cooked on a griddle and made with oatmeal, flour and yeast. They can have a variety of savoury fillings (sweet fillings are also available but frowned upon by locals) and once were sold direct from house windows to passing customers. They are not to be confused with the Scottish biscuit like oatcake, which is an entirely different affair. Incidentally The Oatcake is also the name of a Stoke City FC fanzine; such is its cultural importance to the area and Stoke was home to the last house selling Oatcakes direct to the public. It closed in 2012. I think the thing that most endears Leek to us is that it is an honest town, its people unpretentious and friendly. The first time we were called ‘duck’ I crouched in anticipation of falling masonry. Then it became quaint, a linguistic anachronism. Now it’s normal; we miss it if a shop assistant doesn’t greet us like long lost friends while she scans our groceries and bids us farewell with a hearty “ta-ra duck”. The town seems proud of its heritage but wise enough to know it came at a cost. The landscape has been shaped and bent around the silk industry but the scars don’t so much disfigure the town as lend it character and depth. After all where else could you wander passed an Oatcake shop on a cobbled street on your way to Waitrose? Footnote. I’ve used a variety of sources for my research that is not referenced in the text for ease of reading. This is a blog and not an academic work after all. Nevertheless my sources include: https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/child-labour https://eh.net/encyclopedia/child-labor-during-the-british-industrial-revolution/ http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/staffs/vol7/pp84-169#h3-0007 http://www.localpopulationstudies.org.uk/PDF/LPS74/Article_3_McCunnie_pp54-74.pdf http://www.heritage-explorer.co.uk/file/he/content/upload/11797.pdf http://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/darts/38139647 Welcome back. This is the first in occasional[1] entries while we are off the road. Today is exactly one year since our first proper blog entry; a picture and brief note that we’d started packing (2 March 2017). I miss writing even if it’s a blessed relief to everyone else. So picking up where we left off, we are working at Shallowford in a variety of positions that, for the sake of convenience we’ll place under the umbrella title of hospitality. The work’s good, varied and at times stretches us in good ways. Despite that there is a distinct feeling that we are marking time. We get to spend a night or two a week at our house in Leek, which we love and want to spend more time in. It’s riddled with odd jobs that need doing to turn it from a house into our home but progress is gradual. Plus, because we are spending our time there doing those jobs we are not taking advantage of the glorious countryside around us. Which probably sounds ungrateful but it isn’t intended to be; it’s just that deep down our hearts are on the road and in the hills. To that end we’ve taxed and insured Mavis and are negotiating plans for the summer. There’s nothing definite yet and we feel like we are on a mountain, gradually eliminating options as we focus and close in on the summit. Some we reject out of practicality, some with regret and there are occasional slips and pauses to find new routes but the momentum is ever upwards. And that, you will be relieved to know, is the end of that clumsy extended metaphor. Let us now venture into our surroundings. I’ll get to Leek in the fullness of time, but as we’ve spent most of our time in Shallowford let us introduce you to our nearest settlement of any note. Stone is a modest place that despite being the 2nd town in the borough of Stafford (after Stafford) is so unassuming the chances are that you haven’t even heard of it. There are probably residents of Stone who are uncertain where it is. Even its name means nothing sexier than ‘a stone’. Local legend suggests it is named for a pile of stones that marked the graves of princes Ruffin and Wulfad, allegedly killed by their father King Wulfhere of Mercia in AD 665 because of their conversion to Christianity. This is apparently most unlikely, not least because Wulfhere was in fact a Christian himself by then. Nevertheless Ruffin and Wulfad were canonised, although only St. Wulfad gets to be commemorated by sharing in the name of the imposing C18th church of St Michael and St Wulfad. Quite what St Ruffin did to be left out I don’t know but the pair are still remembered by the pilgrims who walk the Two Saints Way that runs from Chester to Lichfield via Stone, and who bring stones to place in a basket by a church window that commemorates the saints. Stones to Stone is like coals to Newcastle without the practicality of use as a handy fuel. The pilgrim’s way is one of several routes that make Stone if not appealing then at least necessary. It has a railway station and was once a mayor coaching town. Nowadays it sits on the busy A34 and A51 and is a couple of miles from the M6. Its position on the banks of the River Trent means it has been a stopping point for cargo-carrying vessels since Roman times and it held an important position point on the Trent and Mersey Canal, the motorway of its day and was essential in ferrying pottery safely from the nearby pottery towns around Stoke on Trent. The canal still boasts the 1772 Grade II listed Star Lock in the centre of town. It stood for about 24 hours before having to be rebuilt because a cannon fired in celebration of its completion struck the new lock, all but destroying it. Of all the directions to aim a machine built expressly to destroy property and people, someone chose to point it towards their nice new lock on which the paint had barely dried. Honestly, someone had one job to do… Nowadays the canal is for leisure, with a big boat yard on the town side of the lock, which is mercifully free of artillery bombardment and which supports a rather nice public house, ideal repast after a pleasant tow path ramble. Drinkers today are blissfully unaware that the building was once a slaughter house. Before we leave talk of canals…we had a group stay at work from the Canal Ministries. Wonderful people who minister to the canal boat community. They were lovely and do some great work, but someone should tell them that they shouldn’t brand their polo shirts on the left breast with Canal Ministry, because the C is hidden on the more buxom members. Stone town centre is divided into three distinct parts. The main thoroughfare is pedestrianised but has a pervading sense of hanging on. The large CoOp is destined to close soon and it has more than its fair share of charity shops. There are restaurants and shops hiding in narrow alleys radiating from the High Street and a few independent shops and cafes but they all seem to close early, leaving the ubiquitous Costa to mop up business. Below the main street is a cluster of brightly lit takeaways punctuated by the sort of shops that cannot afford a position on the main High Street; a fireplace shop, hairdressers and specialist injury lawyers (or parasitic ambulance chasing evil bastards in the common parlance). The other end of the high street, across another busy road is a neat triangle of shops and businesses that appear more prosperous; a Weatherspoon’s in the old post office, a fancy tea shop, an outdoor clothing and camping specialist and a few hairdressers of the boutique variety. Within easy walking distance of the High Street a large brash Morrisons casts a malevolent yellow shadow over the town, sucking the life from the independent businesses. It’s not that I object to Morrisons, or indeed supermarkets in general (that would be hypocritical considering how often I seem to visit them) but a town the size of Stone cannot support its local businesses when most of the trade goes over the road to the supermarket. On the road we take into Stone there stands a sad little parade, a pub that’s trying a tad too hard to attract custom, a OneStop shop that sells everything that the nearby CoOp sells, only for more money and later into the evening, a brash Shell garage and, sat a little way back like a shy aunt at a wedding, the glorious shrine to cholesterol that is The Walton Fish Bar. We called in one day and, affecting the kind of saunter only a southern dandy like me could pull off I casually leaned on the Formica counter and beckoned a bosomy vision in nylon over and requested two of her finest fresh fried cod and one large portion of chips to share. She held us in her gaze appraisingly, presumably decided we were clearly a long way from home and needed help. “I think you’ll just need a small chips duck” she replied and scurried off to cook them. We then passed a merry half hour helping her remember the name of a song that went “hey hey…” Our meal eventually arrived and, turning to leave I ventured…”was it Hey-Ya by Outkast?” Well, I was hailed a hero and practically borne aloft out of the building. We got home to find the most enormous portion of chips known to mankind which burst forth from a bag made soggy by grease. The portion sizes up here are a thing to behold, full size sponge cakes cut into four, sandwiches with the cheese filling thicker than the two doorstep slices around it and even the Indian restaurant has a whole section dedicated to extra-large portions. Apart from mammoth meals the town has the distinction of having a parliamentary constituency named after it twice, once between 1918 and 1950 and then again from 1997 to the present day. The incumbent MP nowadays is the Eurosceptic Conservative Bill Cash. Of note is his falling out with his journalist son William, played out in the pages of The Telegraph and Spectator. Young William, the little scamp, joined UKIP as its Heritage Spokesman, much to daddy’s irritation. As if that didn’t prove William is a prize knob then consider that he set up Spear’s magazine. If you don’t know Spear’s, and as you are reading this then I’ll assume that you don’t, it is a “wealth management and luxury lifestyle media brand, whose flagship magazine has become a must-read for the ultra-high-net- worth community”.[2] According to their website their readership is made up of people with average assets of £5 million+. I’ll wager they don’t carry handy hints on stretching out the family budget until pay day in the magazine. Aside from super-rich Tories Stone has given birth to some notable sons and daughters. Among them is Eva Morris whose claim to fame was living to 114, several sports stars including footballers Stan Collymore and Anthony Gardner and the inventor of Hovis, Richard "Stoney" Smith who invented the wheatgerm infused bread in Stone. It’ll be familiar to those of us of a certain age from the iconic advert featuring a baker’s delivery boy on his bicycle negotiating a cobbled hill. For all its Midlands appeal, it was invented at Stone Mill and made in Macclesfield, the advert was filmed in Shaftsbury in Dorset and incidentally was directed by Ridley Scot, who went on to make his name with the Alien franchise. On the outskirts of Stone are common grounds known locally as Mudly Pits where in 1745/46 the Duke of Cumberland set up a winter camp for his men, sheltering them from the freezing moorlands and peaks. They were on a mission to intercept the Jacobite’s’ advancing on Derby. In the end the rebels turned back without the Dukes intervention because of the onset of winter. You can read more about the Jacobite rebellion in our entry of 20 May 2016. Now we have been reassured that we can navigate Stone without cannon fire or bumping into royalist forces it has become our go-to place for a pleasant stroll along the canal or a saunter along the High Street in search of bargains. It is a middle of the road town in the middle of the country that isn’t chic and has no real tourist appeal. It is home to stolid people who have seen its fortunes wax and wane as their local economy wrestles with changing industry and technology. In many ways Stone represents the underdog, the backbone of the country where people’s livelihoods have always been for hire and seldom guaranteed. It is clearly trying hard as a community to cope and to find its place in the post-industrial C21st and the signs are that its fortunes are slowly looking up. There are new, prosperous looking homes being built, the High Street is freshly paved, the tow path and lock are getting a makeover, new restaurants and wine bars are trying their luck and there’s a feeling that spring is just around the corner. Over in Leek we have just finished sorting out furniture and we had a washing machine delivered on the 2nd attempt. On the first attempt the driver opened the van, scratched his head and eventually apologised because he’d forgotten to load the washing machine in. Honestly, someone had one job to do… It finally arrived the following morning which gave me an opportunity to swagger around looking faintly butch with a tool kit, although the effect was rather undermined when I used a toilet roll tube as part of my plumbing-in (don’t ask). That aside we’ve adopted a splendid pub as our local and been on a brief expedition exploring walks around our area, including an exciting walk/slide down an almost vertical (at least to us southern softies) hill. Alison blamed her new walking boots, honestly, they had one job to do… [1] I.e. When I can be bothered. [2] http://www.spearswms.com/about/ |

IntroductionThank you for stopping by and reading our blog. If you don’t know who we are, what we are doing and you're wondering what this is all about you can read up on our project here. Archives

November 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed