Our Travel blog

What do darts champion Eric Bristow, Dave Hill, vocalist with heavy metal legends Demon, the founder of the Arts and Crafts movement William Morris and James Ford, one half of electronic duo Simian Mobile Disco and producer of artists including Artic Monkeys and Florence & the Machine have in common? Well, they all live in or have close ties to Leek in Staffordshire. Of course a chubby bloke who throws pointy things and thinks victims of child abuse are not ‘proper men’, a couple of musicians barely known outside of their front door and a revolutionary socialist designer of flowery wallpaper hardly make Leek the epicentre of culture, but it’s something. Morris visited in 1875 and stayed on and off for three years with his friend Thomas Wardle, a silk dyer who operated the Hencroft Works in Leek. Labouring together they improved organic dyeing techniques for textiles, the racy pair of scallywags. Importantly though, Morris had his eyes opened to the conditions the mill workers had to endure and his time in Leek influenced his left leaning politics, although paradoxically his designs found patronage among the middle and upper class or as he as he put it "ministering to the swinish luxury of the rich". Before Morris swaggered into town Leek had already played its part in revolutionary politics. During the civil war it was staunchly Parliamentarian, driving those pesky Royalists away and the local garrison played its part in the fall of Stafford. Later, in 1842, Josiah Henry, a 19 year old shoemaker from the town was shot through the head and killed by troops at nearby Burslem. Josiah had been among a ‘mob’ of Chartists, marching and generally rioting in protest against their poor working conditions and the corrupt political system of the day. Stoke and the potteries were among a number of poor industrial areas where the Chartist movement took root. Their demands were not unreasonable by today’s standards:

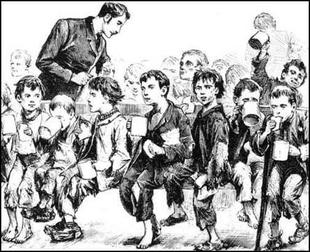

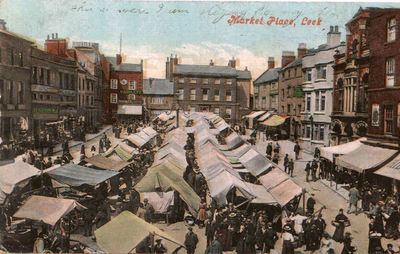

As you can see we meet or exceed all bar the last one nowadays and I for one am happy to avoid the administrative burden and expense of annual elections. Poor Josiah was, at just 19, a widower with 3 young children when he was felled protesting against corruption and injustice. Not much else seems to be known about his circumstances but the silk mills, which by the end of the 18th century employed around 2,000 people in the town and a further 1,000 in the wider neighbourhood were notoriously grim to work in. Significant portions of the workforce were children, often from local workhouses. High numbers of orphans meant local authorities were only too willing to place the children in the care of the mills to save them the expense of raising them. In the mill they would begin work aged around nine in return for food, lodgings and if they were lucky one hour of schooling a week. The hours were long and the work unpleasant and at times downright dangerous. The Macclesfield Courier printed this in May 1823, “A little girl about seven years of age was caught by her clothes and drawn between an upright shaft in the engine room and a wall…..life was extinct”. It’s just one of many such entries in the local press of the time. As if the hours weren’t punishing and the conditions weren’t hellish enough, the children were controlled by brutish stewards or ‘overlookers’. On 23rd November 1833 The Macclesfield Courier reported on the death of 11 year-old Sarah Stubbs, who worked as a ‘piecer’ in a Macclesfield mill, the inquest revealing that she was repeatedly beaten for not tying broken silk threads at the required rate. The work of children was sanctioned by law. The Cotton Factories Regulation Act of 1819 set the minimum working age at 9 and maximum working hours at 12 and later the Ten Hours Bill of 1847 limited working hours to 10 for children and women. Ironically in the early 1800’s the silk mills were considered relatively benign places for children to work, to the extent that they were exempted from the child labour laws for a time. Looking back on it now the children working in the coal and lead mines were worse off but when we’re talking about 10 year olds it’s all relative. It’s worth pausing here to note that the appalling working conditions children had to suffer in this country up to the 20th century are still endured by children around the world today. According to The International Labour Organisation the global number has declined by one third since 2000 but there are still 168 million in child labour with 85 million of those in hazardous work. Article 32 of the UN Convention on the rights of the child states: “Governments must protect children from economic exploitation and work that is dangerous or might harm their health, development or education”. I fear though that the UN article may just be a nicely worded piece of spineless liberal guilt. Case in point; as well as the 45 Articles there are 3 additional protocols that are optional; governments that ratify the Convention can decide whether or not to sign up to them. The protocols are: the sale of children, child prostitution and child pornography, the involvement of children in armed conflict and a complaints mechanism for children. Just to be clear then, it is 2017 and selling children, involving them in prostitution and pornography and sending them to war is optional. FFS! Back in the 1800’s a Parliamentary enquiry eventually uncovered and publicised some of the unsavoury conditions which did lead to improvements. Nevertheless children were still employed until the Education Act of 1880 introduced compulsory schooling up to the age of 10 and child labour began to dwindle. Subsequent amendments raised the school-leaving age to 12, with dispensations to leave before this age if pupils reached the required standards in reading, writing and arithmetic. By the end of Victoria's reign, almost all children were in school up to the age of 12. I’ll give the last words about it to 10 year old Samuel Downe, giving evidence to a parliamentary enquiry in 1832. ‘We used to generally begin at five o ’clock in the morning till eight at night’. When asked had he received punishment he replied ‘yes, I was strapped most severely till I could not bear to sit upon a chair without pillows, and I was forced to lie upon my face at night. I was put upon a man’s back and then strapped by the overlooker’. When asked why he was punished he replied… ‘I had never been in a mill where there was machinery, and it was winter time, and we worked by gaslight, and I could not catch the revolutions of the machinery to take the tow out of the hackles; it requires some practice and I was timid at it.’ One thing the mill owners did do towards the turn of the century was build housing for the workers and their families. Thus by 1878 Livingstone Street in Leek was on the map, typically industrial red brick housing of 123 mostly terraced abodes, each with a small yard complete with privy backing onto a cobbled alley. The cobbled alleys are still there, as they are all over Leek, glorious in their evocation of a bygone age. But lest we sentimentalise too much, today Livingstone Street has mains drainage, indoor plumbing, central heating and refuge collection. We have now made one of these former workers houses our home, extended sometime in the intervening years to incorporate a bathroom and a nice kitchen with gas at the flick of a switch rather than us having to fetch coal in for the range. I’m under no illusions about coal fires and range cooking. We had coal fires when my parents moved us to Suffolk. Bewitching as the crackling flames and flickering glow was the fire needed careful nurturing all evening and only heated a semicircle of our living room to a radius of about 3 feet; anything inside the heating zone would steam and wither while anything outside froze. I spent many a winter evening on the threshold of the magical sector slowly revolving like a chicken on a rotisserie. Every 15 minutes or so a plume of acrid smoke would puff back into the room where it joined the fug from my father’s cigars to make my eyes sting and add another layer to the brown patina of the ceiling. On a bad night I’d bend double and cough up my dinner while my hair singed and my bottom turned to ice. In between these smoky interludes I kept busy trying to avoid the red hot embers the fire would occasionally spit out. These tiny volcanic bombs would burn on contact with flesh, burrow a smoky trail through clothes and occasionally ignite the dog. My school blazer looked like it belonged to a clumsy chain smoker who lacked opposable thumbs. Garments dried on the old wooden clothes horse in front of the fire would crisp and stiffen up like board. I once made my freshly dried trousers stand up by themselves and then balanced a shirt on top to create a freestanding dummy fresh from the clothes horse. Well, it was a long winter and there wasn’t much else to do. We had one radiator in the house, essentially an overflow for the coal fired back boiler in the range. It was in my bedroom and worked a treat, so long as you didn’t mind acrid desert conditions all summer and artic winters. If I turned it off in the summer the whole system would rumble ominously and steam would escape from mysterious valves in the bathroom. If I turned it on in winter my room just got colder. The whole system was a mystery to my parents and, it turned out, to the local plumber too. I woke up one morning to a fountain of scalding water arching across the room onto my bed. The plumber turned lots of valves and taps that had no noticeable effect, hit pipes with a hammer and generally walked about the place looking bemused. Eventually he repaired the radiator with some sort of putty and what looked suspiciously like a used bandage and I was advised to move my bed further away. My mother used the coal fired range for cooking, which meant it cooked with the power of a match under a cauldron or with the heat of a medium sized star. Added to this was her charming belief that the food would be ready when she was, in spite of the wildly fluctuating temperature of the oven and her aptitude for getting distracted. Remarkably dinner was always ready at 5.45pm. If, that is, we accept the premise that ‘ready’ means it’ll be served up in whatever state it happens to occupy at 5.45pm while on its haphazard journey from rare to carbonized. So, we’ve decided against open fires. In other respects we have a mission over the coming months to undo some of the more flamboyant DIY a previous owner has attempted and to do a little light decorating here and there. But it’s a great place to live, cosy and homely and the toilet is inside. Sitting on major trans-Peak roadways Leek has long been a transport hub. The major roads had lucrative turnpikes and it was connected to the canal system as a branch of the Caldon Canal, which closed in the 1940s. The railway lasted until the 1960s when Dr. Beechings got his grubby hands on it. A street down from us now houses the bus station and an ugly parade of 1960s shops well past their prime, built on the site of the old cattle market. Just along the road things improve dramatically however. At the foot of the High Street is the Nicholson War Memorial. Built in 1925 and clad in pale Portland stone it stands an impressive 90 feet high with a large clock face on each of its four aspects. Over the road from the memorial the high street crowns the hill Leek sits upon, with an ancient market square at its apex. Granted a charter to hold a market on Wednesdays during the reign of King John at the beginning of the 13th century the market is still a regular local fixture. The High Street came second in the Telegraph's High Street of the Year in 2013, losing out to Deal in Kent. I’m not sure it would do so well now, it’s not gentrified like Southwold or touristy like nearby Buxton, but its charms are still there in the details; original wooden hitching posts along the street, the cobbled market square, independent shops and cafes, a surfeit of busy pubs and echoes of the arts and crafts movement heralded by William Morris. Look up as you walk along the high street and there are fine stained glass windows in unexpected places, examples of elaborate plasterwork above anonymous shops and little architectural gems down narrow alleys and side streets. Just past the market place there is a large civic park that drops away dramatically from the sombre St. Edward the Confessor church into a narrow gully and rises again through woodland to less formal lawns, a bandstand and tennis courts. It’s most comely in its sprawling semi-formal way, a nice contrast to the rugged moorlands that lay beyond. From the high points you can see the chimneys and spires of Leek over the trees. Although it’s on a hill Leek appears to sit in a bowl surrounded by the higher Staffordshire Moorlands and Peak District to the North and gentler hills to the South and West. Eastwards lay the heights of Mow Cop, which you can read about in our entry from 7th June 2016 if you feel so inclined. It’s an interesting place in an industrial heritage kind of way. It’s no Florence of the Midlands but architecturally it does wear its manufacturing past well. Some streets close to us are still cobbled, abandoned silk mills pop up around street corners, some converted into offices and warehouses, some apartments and others sit abandoned and derelict, casting sinister shadows over the surrounding houses. These are ripe for re-development; when we were looking for a place to buy we were shown round an apartment for sale inside the converted Waterloo Mill and it was stunning with high windows and great views. It was gratifying to see the building preserved and repurposed. On a drab wet Tuesday recently we walked to the Sainsbury’s store on the edge of town. It is down the hill from the town centre, on the banks of the River Churnet and next door to Brindley Water Mill, an 18th century corn mill that’s still in working order. Standing in the drizzle on open ground between these two contrasting buildings we could see the open moorlands curving around us capped in fresh snow, the line between grass and snow almost ruler straight. Before the hills lay lush green pastures topped with barren winter woodland and stone farm buildings on level ground hewn out of the tumbling countryside. It reminded us that for all the necessity of convenience foods and toilet roll what we really needed was to get out into that open moorland with a backpack, map and trousers with too many pockets in. But, we both silently concluded, when it’s a bit warmer. Walking back we diverted by the back streets, rows of terraced homes like ours which revealed another of Leeks charms; small out of town shops and businesses. This was a real revelation. Nearly every residential street has a corner shop of some variety. Some are convenience stores, some chip shops, others bakers, sandwich shops and more than any other, hairdressers. Maybe it’s the windy conditions that force the population to get their hair done so regularly. I counted 36 different hairdressers on one website and that doesn’t mention a few that we’ve passed on our explorations. In keeping with hairdressers everywhere they excel in crappy pun names. Our favourite thus far is “Curl Up And Dye”. I just love the idea that small, almost micro businesses are so prolific in a town with at least 6 main supermarkets in or around it. Worth a mention here is our local Oatcake shop. For those unfamiliar with the culinary phenomenon that is the Staffordshire Oatcake it’s a savoury pancake cooked on a griddle and made with oatmeal, flour and yeast. They can have a variety of savoury fillings (sweet fillings are also available but frowned upon by locals) and once were sold direct from house windows to passing customers. They are not to be confused with the Scottish biscuit like oatcake, which is an entirely different affair. Incidentally The Oatcake is also the name of a Stoke City FC fanzine; such is its cultural importance to the area and Stoke was home to the last house selling Oatcakes direct to the public. It closed in 2012. I think the thing that most endears Leek to us is that it is an honest town, its people unpretentious and friendly. The first time we were called ‘duck’ I crouched in anticipation of falling masonry. Then it became quaint, a linguistic anachronism. Now it’s normal; we miss it if a shop assistant doesn’t greet us like long lost friends while she scans our groceries and bids us farewell with a hearty “ta-ra duck”. The town seems proud of its heritage but wise enough to know it came at a cost. The landscape has been shaped and bent around the silk industry but the scars don’t so much disfigure the town as lend it character and depth. After all where else could you wander passed an Oatcake shop on a cobbled street on your way to Waitrose? Footnote. I’ve used a variety of sources for my research that is not referenced in the text for ease of reading. This is a blog and not an academic work after all. Nevertheless my sources include: https://www.bl.uk/romantics-and-victorians/articles/child-labour https://eh.net/encyclopedia/child-labor-during-the-british-industrial-revolution/ http://www.british-history.ac.uk/vch/staffs/vol7/pp84-169#h3-0007 http://www.localpopulationstudies.org.uk/PDF/LPS74/Article_3_McCunnie_pp54-74.pdf http://www.heritage-explorer.co.uk/file/he/content/upload/11797.pdf http://www.bbc.co.uk/sport/darts/38139647

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

IntroductionThank you for stopping by and reading our blog. If you don’t know who we are, what we are doing and you're wondering what this is all about you can read up on our project here. Archives

November 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed