Our Travel blog

|

On a recent day off we took ourselves to the remote settlement of Croggan. It sits at the tip of a peninsula of corrugated land between the sea and Loch Spelve. Its remote feel is partly due to the effort needed to get there. Historically it would have been by boat but nowadays a single track road winds its way sluggishly between hill and sea, passed jutting rocks and over tumbling burns. In places where it hasn’t been patched up rough island grass grows down the centre and passing places are few and far between. This absence of passing places gives rise to occasional passive games of chicken when you come nose to nose with an oncoming car. On most roads here there are plenty of passing points and after a while you learn to time your approach to such a degree that neither party has to slow down significantly. On our journey to Croggan, having already negotiated sheep, cyclists and geese we had to reverse back over a hillock and then further on we had to force some ridiculous tank/4X4 hybrid to reverse for a ¼ of a mile. On this last occasion we took the high ground, literally and figuratively as we rounded a bend to come face to face with them parked up in the middle of the road taking pictures. After parking overlooking the narrow entrance to the loch we walked on a rough track around the peninsula, carefully avoiding a young Adder slithering across the track in front of us, and onto the secluded sandy beach of Port nan Crullach. It was a hot day and we shared the expanse of warm sand with one other family and some sheep. After a picnic lunch we paddled in warm waters and lazed on the rocks to dry off. Suitably refreshed we set off for our next destination scrambling up a steep incline through thick undergrowth. The remains of the settlements of Barnashoag and Balgamrie sit in a slight hollow alongside a spring fed burn that tumbles off the cliff in a series of waterfalls and onto the beach below. Or usually does; the unusual dry spell meant it was almost dry today, making our assent easier. This must have been a tough place to live; isolated, even by Mull standards, the rudimentary stone crofts comprised around 23 buildings and enclosures that were exposed to vicious winter winds and humid midge infested summers. These particular settlements were deserted towards the end of the 19th Century, along with many such places in Mull. From the mid-18th Century to the end of the 19th the population on Mull shrunk from around 10,000 people to under 3,000. Indeed the Highlands of Scotland and Western Isles were reduced to one quarter of its population in the same period. Popularly dubbed The Highland Clearances the reasons were more complex than sometimes reported but essentially were the result of greedy out of touch and mostly absentee owners of the land. And I use the word owners in the loosest possible sense. Mostly they were the traditional Clan Chiefs who were keen to move into polite Edinburgh and London society and ‘improve’ themselves. They may have believed that they owned vast areas of Scotland, but they were cash poor, relying on their tenants paying a paltry rent via middlemen, or Tackmen, who collected the rents and essentially ran the settlements and oversaw their Chief’s land. Then came the sheep. Scrawny local sheep had been a staple of the small holdings but now a hardy Cheviot cross breed that could withstand the harsh winters was introduced and slowly spread in a bleating tide of mutton and lamb. To facilitate maximum return from their herds the landowners drove the tenants out. Initially through the Tackmen, who imposed impossibly high rents, and then by militia, friends and neighbours of the gentry and finally the army. There were revolts but they were largely unorganised. The church ministers, translating for their lords and masters from English into Gaelic, encouraged the populace to move on with threats of eternal damnation, claiming the abundant grasslands of the glens and hills were needed to fulfil God’s plans to graze sheep. The locals were viewed as vulgar, superstitious, idle and incapable of ‘improvement’. The landowners, or their representatives at least, resorted to the burning of crofts and other harsh treatments. According to contemporary accounts it was the women who put up most resistance. For example in one incident at Strathcarron in March 1854 the police force clashed with such ferocity with women blocking their path that their batons were broken on the bonnets of the protesters. There were just 2 men and a couple of children present to support the women. No injuries to their ranks were reported by the police but fatalities and life-changing injuries were widely reported among protesters. Gradually shooting estates replaced sheep in some regions, vast areas given over to grouse, deer, hare and other game rented out to syndicates of noble gentlemen for their leisure, leading to more clearing of the settlements that still lingered in the glens. Then famine struck. Potatoes were a staple crop in the highlands and islands, a cheap crop that could grow in the poor soil and could survive being buried in pits ready to be dug up in the spring. Potato blight swept through Europe in the 1840’s and decimated Ireland from 1845. In 1846 it crept into the Western Highlands and hit its zenith in 1847. Grain was still harvested but was sent south to keep English stomachs full, causing riots and the intervention of the army. Highlanders, already driven to the margins, starved. Eventually relief came, some from the mostly absentee landlords but generally through charity relief from the lowlands and England. A lot of this was dependent upon the people being ‘deserving poor’ and local ministers had to vouch for the family’s standing and good character for them to get any help. Work schemes were introduced to provide labour in return for meagre supplies by the more ‘enlightened’ landlords. The biggest form of relief though came in the form of emigration. Highlanders had been emigrating for some time in response to the clearances but now it gathered momentum. People were encouraged, lied to, forced and all but herded onto any old creaking ship that would transport them to Canada, America or Australia. Promises of a utopian better life were made and people crowded into ships with no privacy. Many didn’t survive the voyage as cholera swept through the over-crowed hulls and food and water ran out or was contaminated. Struggling ashore they encountered bleak, harsh conditions and little to sustain them on unfamiliar foreign soil. Many ended up destitute again. Free were the fields of fern Free was the fishing in the coves of care Empty are the homes of old Empty for the sake of summer's cause Yes, you're taking it all away The music, the tongue and the old refrains You're coming here to play And you're pulling the roots from a dying age. Jim McLean Incidentally, a lot of what we think of as highland culture doesn’t come from the Gaelic speaking natives. They might well have worn a practical kilt, coloured according to the supply of local materials to make dye and patterned by local weavers but tartan as we know it today, along with all the impractical adornments like bejewelled dirks (daggers worn on the kilt belt), sashes and ridiculous hats were an invention peddled in no small part by well-heeled gentlemen of dubious Scottish legacy. They formed groups like The Society of True Highlanders and The Celtic Society of Edinburgh in the early 1800’s to peddle a fashionable faux nostalgia for all things Scottish, to celebrate the very heritage that they were eradicating by their greed. President of the Celtic Society was Sir Walter Scott (author of Rob Roy & Ivanho) who managed to get King George IV north of the border, the first foray into Scottish territory by an English monarch for 200 years. It was Scott and his assistant David Stewart who prescribed official tartans for each ‘clan’. This may not have been as cynical as it sounds. Following the Battle of Culloden in 1746 an Act of Parliament was passed which made the wearing of tartan a penal offence. Over time the details of the old patterns were lost and old tartans perished leaving limited evidence for Scott and Stewart to work with, at least for some of the smaller Clans. The fashion for all things ‘Scottish’ was an invention of the ruling landowners and high society who romanticised the Highland life. People carrying the clan surname were mostly not related by blood anyway, their ancestors probably took the name of their Clan Chief because they lived on his land. Anyway, in spite of its severe and unforgiving history we found Barnashoag and Balgmrie enchanting on a sunny day. It is to the credit of the Scottish that little settlements like these stand as remote testament to the dispossessed. There are no signs, information boards or even paths, just remote ruins on a lonely windswept hilltop looking out to views that few of the villagers would have appreciated in their harsh hand to mouth existence. [1] Following animal tracks down the hills we came upon a more complete cottage whose walls were almost intact. It sat next to a burn that tumbled over the rocks in a series of small noisy waterfalls, into a thicket of gorse where a young deer had taken refuge as we approached. Across the stream was a walled animal enclosure and the remnants of old stone walls, one of which we traced downhill to the track and back to our car. The Cheviot sheep certainly took to life on Mull and are still present in huge numbers just about everywhere you look. On the way into work the other day we were driving along at a sedate pace and rounded a corner to be confronted by a small flock of them in the road, a not uncommon occurrence here. However this bunch proceeded to sprint ahead of us on the road, ignoring the lush grass verges and open fields to either side. Clearly seeing their chums having such fun more joined them from the undergrowth until we were surrounded by galloping woolly ruminants. Alison, glancing in the rear-view mirror squealed “Oh my…I’m about to be overtaken by a sheep…” and sure enough we were. A first for us and it has replaced the Robin Reliant that was Alison’s previous personal best in the ‘being overtaken by…’ competition. In fact I think it might beat my horse and cart entry. We’ll let you be the judge. Alison is of course a rock of sweet midge bating loveliness as always and has discovered a passion for wandering off-piste over hill and glen in true Scottish fashion. So liberal are the local laws regarding access to land that in most circumstances you can just wander wherever takes your fancy, so much so that even the Ordinance Survey maps don’t show footpaths. In itself that’s rather fabulous but it does mean that on occasion one will scramble up a promising ridge to be confronted by an impenetrable deer proof fence with smug looking sheep on the other side and no option but to retrace your steps or wander further. We can walk for miles without seeing another soul; it’s all quite splendid and makes for exciting escapades.

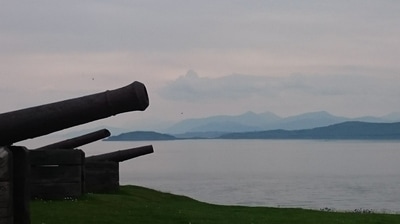

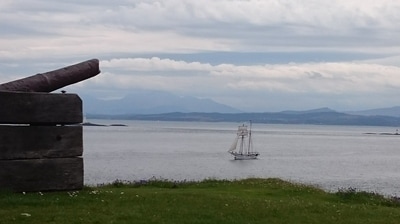

When not off roaming the hills or at work, we’re very comfortable here in Mavis in our quiet little corner of Mull. We’ve been very lucky so far with the weather. What we particularly appreciate though is the breeze; it keeps the midges away. If Scotland is known for anything that cannot be dressed in tartan and sold to American tourists its midges. We’ve only had a couple of days when the little buggers were around in significant numbers so I guess we should count ourselves lucky. One of those days happened to be when I was alone in a little shed selling entrance tickets to the castle. It was warm, raining lightly and mild so I had the window shut until a family approached who were performing what I think of as ‘the swatting dance’. This involves walking along at a brisk pace waving your arms about your face and every few paces slapping the back of your neck or cheek then back to the arm waving. I think it may be a distant ancestor of Morris dancing. I had no option but to open the window to serve them and thus my afternoon was spent in the company of approximately seven billion insects. I’m fortunate in that they don’t seem to bite me, unlike poor Alison to whom they are understandably attracted. If you keep moving they are fine, but stand still and they go up your nose, in your ears and settle on any exposed skin. In my little hut that afternoon I experienced all this plus the added misery of them sticking to the midge repellent I’d sprayed on. By the time I swapped over with the other guide my face looked like I’d spent the afternoon tattooing it. Mind you my replacement was sporting a kilt so I felt I couldn’t complain, I just gave him a sympathetic look and wandered out looking like a Māori version of Pigpen from the Charlie Brown cartoons. Finally I’m aware this year’s blog isn’t taking the same shape as last years, and that the posts are far less frequent. Apologies for that but work and recreation in the form of discovering this glorious island is our priority while the weather lasts. If I’m honest I’m not feeling the passion for writing that I had last year either. It may be this working full time nonsense (honestly, whose idea was that?) or just that I find myself lacking sufficient vocabulary to do this wonderful place justice. Hopefully the photos accompanying the blog will do the job for me. As the saying goes a picture paints a thousand words.... [1] In my clumsy attempt to summarise a complex and nuanced situation I’ve glossed over an awful lot of detail and simplified events to a ludicrous degree. I’m indebted to the following books for information: White People, Indians, and Highlanders: Tribal Peoples and Colonial Encounters in Scotland and America – Colin Galloway and Highland Clearances – John Prebble.

0 Comments

Leave a Reply. |

IntroductionThank you for stopping by and reading our blog. If you don’t know who we are, what we are doing and you're wondering what this is all about you can read up on our project here. Archives

November 2017

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed